|

Whaling With

Savik Crew in Spring and Fall

Excerpts from The

Whale and the Supercomputer. I took these photographs at the

same time as the events described (the photos do not appear in the

book).

|

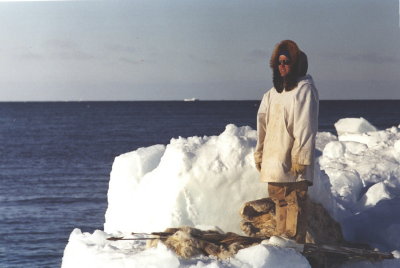

Ultimately, Richard Glenn (at right)

abandoned the degree with only the

writing of the dissertation left to do. Partly, life became too busy

with

’Berta’s arrival and the gas field project to finish. But he also

became

uncomfortable with the idea of having the degree at all. He saw a lack

of

Iñupiaq humility in the basic assumption of his project, the

idea that he could

take traditional knowledge to a higher, scientific level. Through two

years of

study, he had discovered how little he really knew. What he had learned

instead

was that traditional knowledge existed as an organic part of a person

living in

the environment, a whole world constructed from experience, and

couldn’t be

extracted and rationalized into datapoints. “I didn’t want to become

the ice

man, the expert in a town full of experts, some kid from California

that thinks he knows everything,” he said. “To me, it’s not so much

about

finishing a degree as continuing to learn about this life.”

As he made that statement, Richard

stood on white ice in

pale sunlight, gazing over the sea from inside the hood of his white

hunter’s

parka. We snacked on a frozen caribou haunch. The waves were up a bit,

so Savik

Crew was not boating, instead just waiting for a whale to surface

nearby, the

harpoon and shoulder gun laid out with care at a high

point on the ice edge. Waves boomed and

reverberated

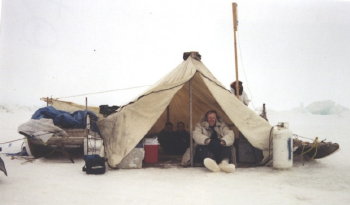

underneath, so Richard had moved the snowmachines back a little; the

camp with

the tent was well back among the multi-year ice. My questions were a

distraction from his quiet watching until I asked one that really

interested

him, made him think: which way did he know more about ice, as a

scientist or as

an Iñupiaq? He debated with himself a bit before he answered: He

knew more as

an Eskimo. Scientists, he observed, know a collection of facts about

ice;

Eskimos know ice itself. “The best ice scientist is almost an

Iñupiaq,” he

said. “If he’s a good ice scientist, then he’s thinking the way these

people

here do.”

|

|

|

|

First light showed an ocean perfect

for whaling. A rich rim

of gold emanating from the eastern horizon held up a sky dome of

velvety blue.

Roy and his crew climbed the high gunwales of Savik Crew’s fall whaling

boat

while it still sat on the trailer and Richard took the wheel of the

pickup

truck to back it down the ramp on the beach near NAPA.

Then he unhitched and left for work. Lots of boats and crews were

launching and

floating just offshore. The air was sharp with the fall chill and the

excitement of the moment amid the scent of the sea and fuel. Roy

opened the bomb box and prepared the weapons, heavy gear thumping on

the fiberglass

deck, sounds flattened by the surrounding sea. Eben took his place with

the

harpoon ready on the foredeck. In the aft, the grub box yielded metal

Thermoses

of hot coffee and store-bought cinnamon rolls. Roy

pushed the throttle lever forward and we flew out into the Arctic

Ocean, directly away from Barrow. A long swell from the

north

lifted us in slow rhythm

These waves came from far away, built

over hundreds of miles

of open water where the pack ice had retreated. A few months later,

scientists

from Boulder confirmed its unprecedented distance when they announced

that the

ice had shrunk farther than ever before measured with passive microwave

satellites first launched in the 1970s, the result of a warm, stormy

summer

that broke and melted the pack. Arctic sea ice was smaller than the

long-term

average by a million square kilometers, or 14 percent, and much of the

retreat

was on the Alaska and Siberia

side. The ice also was thinner and less compact, even at its center.

Jim

Maslanik, a co-author of the study, said the ice extent was probably

the lowest

in fifty years. It was as if a continent were disappearing.

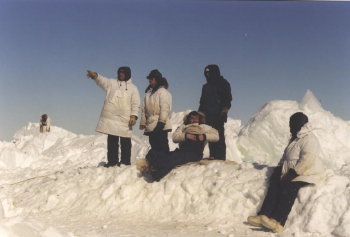

(Eben at top, Roy center, Savik at bottom.)

|

|

|