All rights reserved. Click at left to learn more.

|

Charles

Wohlforth All rights reserved. Click at left to learn more. |

| Whaling

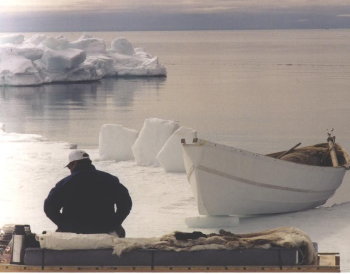

With Oliver Leavitt Crew Excerpts from The Whale and the Supercomputer. I took these photographs at the same time as the events described (the photos do not appear in the book).

|

|

Sitting on the sled, Oliver was looking for

whales and

gauging the ice. In traditional spring whaling the umiaq perches

on the ice edge ready for launch. If a whale surfaces

nearby, the crew launches as quickly and quietly as possible and

paddles to the

whale or to a spot where the captain expects the whale to resurface.

For the

harpooner to hit the whale’s vulnerable spot, just behind the skull,

with a

harpoon made from a long pole of heavy lumber, the captain has to

maneuver the

boat right onto the whale’s back or within touching distance alongside.

The

whale can move much faster than the boat, so most of whaling is waiting

quietly

for a whale to come close enough to launch. In camp, no bright colors

are

allowed that might catch a whale’s eye and crews avoid unnecessary

noise and

movement. Hunters wear white, pull-over parkas lined with caribou hide

for camouflage

on the white snow. That morning we saw only one whale, a far-off black

back

rolling across the surface, and heard another, a roaring blowhole

exhalation

from somewhere we could not see, hidden by the ice. Normally at this

time of

year, a crew would be seeing whales every few minutes. Crews farther

down the

lead were paddling in search of one, thinking the migration might be

passing by

on the other side of the big ice across the lead.

|

|